Listen Magazine Feature

a life with billie holiday

by Lara Downes

Every Saturday morning when I was a little girl, my sisters and I went to the San Francisco Conservatory of Music for what we called “Saturday Classes”: piano lessons, theory, music history — serious classical music training for serious little musicians. Saturday afternoons, when we got home, we had a ritual. We’d get out our “dress-up” from the vintage steamer trunk that housed a collection of my mother’s 1960s party dresses and my grandmother’s furs, go through my parents’ record collection — The Beatles, Sinatra, Charles Aznavour, Nat King Cole, Billie Holiday — and dance around the living room. Those Billie Holiday records stopped me in my tracks. I was enthralled by her dark eyes shaded by the white gardenia, by her world-worn voice, and by what I knew, even then, to be the totally, startlingly distinctive qualities of mood and phrasing, line and color that she brought to even the simplest tune.

In my diary, the year I was eight, I made a careful list, in perfect cursive, of all my favorite things. My favorite song: Billie Holiday, “I Cover the Waterfront.” Such a sad song, about watching and waiting for a love that’s gone. That year was the last year of my father’s long, slow dying. And then he was gone, and I spent foggy afternoons at our dining room window, looking out over the San Francisco Bay, waiting for the sadness to lift. I pulled out the old records at night. I cover the waterfront, Billie sang, I’m watching the sea / Will the one I love be coming back to me?

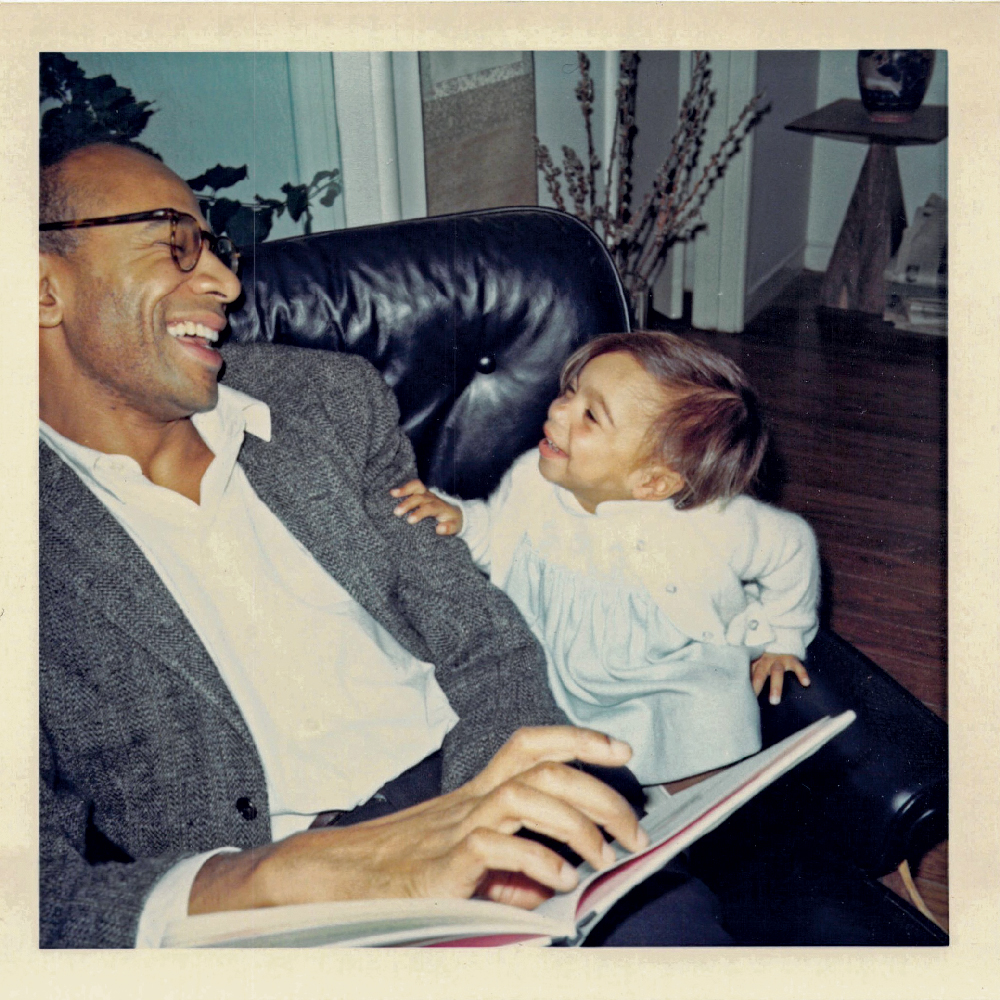

My father was born in Harlem, and he grew up just steps from the legendary clubs where jazz blossomed in its golden age. The Apollo, Lenox Lounge, Minton’s: all places Billie Holiday sang during the years of his childhood. He loved jazz, and in my earliest memories he is listening to records, the long length of him stretched out in the Eames chair in our living room — Billie Holiday, Ellington, Coltrane, the Modern Jazz Quartet, and Glenn Gould’s Bach, which is its own kind of bebop.

In the end, he left us the memories and the records.

My sisters and I buried our loss in our music. My mother took us to Europe, where we lived in the great capitals and studied at the great conservatories with the legendary artists of a quickly vanishing generation. It was a very different life, surely, than the one my father had imagined for us. I studied Mozart and Beethoven, Brahms and Liszt, with teachers who could trace their own musical lineage back to the source. American culture was something far away, accessed through overdubbed TV reruns, the occasional jar of peanut butter from an army base commissary, and the cheap East Bloc bootleg jazz CDs we bought at open-air markets.

My sisters and I buried our loss in music.

My sisters and I were growing up. I had my first love affairs, with Italian and French and Austrian boys. I spent one impossibly cold winter in Vienna practicing Schumann all day and listening to Billie Holiday all night, missing a boy who was an ocean away. Schumann and Lady Day both knew a thing or two about heartache. I’ll be looking at the moon, but I’ll be seeing you.

Ten years later, I moved back to the States and left my family across the ocean. I made my way, very alone, through the unknown landscape of the New York music world. Nothing I’d accomplished abroad — competition wins, concerts — mattered. I was starting over, and it was hard. There were moments of despair and defeat. I practiced Ravel and Liszt all day in a windowless New York sublet, and listened to Billie Holiday records all night. Beautiful to take a chance, she sang. I found new courage and took some chances, and had some astonishing luck: a competition win, a recording contract.

I was hungry for American music, for a reconnection with what was, after all, my home. I started listening to jazz and all the American pop music I’d missed in a decade abroad. I started playing music by Copland, Roy Harris, Gershwin, Bernstein, and Ellington. There was something about myself that I needed to find in a musical tradition “beyond category,” as Ellington put it — a musical sea made of waves of immigration and tides of change.

Music history. Billie Holiday (above) never learned to read music.

On my bedside table I have two studio photographs from the 1930s. My two grandmothers: Fay, one of seven sisters born to Jewish immigrants from the town of Belz in the Ukraine, who grew up in Buffalo, came out to San Francisco when my mother settled there, lived just a few blocks away from us when I was little, whose story I wish I knew better. And my Jamaican grandmother Ivy, who moved as a young woman to Harlem and died when my father was very small, whose story is lost to family history and memory except for the equation of nose and cheekbones that I see whenever I look in the mirror.

My own story of race and roots is captured in these two faded portraits. Two beautiful women, looking out at me in the bloom of youth and the stylized hairdos of their era, quite literally framed inside the parameters of a time during which any relationship between them would have been buried under layer upon layer of impossibilities and prejudices. Looking into their eyes, I see proof of how much change has come in two short generations, how recently their granddaughter’s version of American life became possible.

My parents met at a sit-in in San Francisco in the mid-Sixties, and they dreamed for their three caramel-colored girls of a New World A-Comin’, a future color-blind America in which race, finally, wouldn’t matter. But of course it did. From the beginning, I was well aware of the undercurrent of racial complexities and complexes that runs through our culture. Being caramel-colored in America, no matter where or when, comes with a burden of confusions and assumptions and unresolved questions. Living abroad lifted that burden for a time. I cried a river of happy tears the night Barack Obama was elected president, so hopeful that maybe, in the shifting tides of a new century, we’d come closer to my parents’ dream.

Family history. Downes shares a laugh with her father during her childhood.

Some years ago, on a Sunday morning, I decided to visit St Philip’s Church in Harlem, where my father was an altar boy, carefully shepherded through his boyhood by the elders of the church and his godmother, Miss Mac, who raised him after his mother died. It was June, a sweltering day, and European tourists were lined up around the block at the famous gospel churches. But St Philip’s is something different — an Episcopal church founded in 1809, one of America’s oldest black churches. The sanctuary was grand and hushed; the ladies wore hats. The service was quiet and formal, with decorous hymns. It wasn’t until the rector started his special sermon that I realized it was Father’s Day — not a holiday I’m in the habit of celebrating. Feeling, again, the permanent loneliness of a fatherless child, I practiced Bach all that day, and listened to Billie Holiday at night. In my solitude you haunt me, she sang.

A musician is born and then made. Everything folds together: every single one of my musical influences and experiences has come together to shape me into the musician I am today. So when I decided, a few years ago, to try to pay tribute to Billie Holiday in solo piano arrangements of her songbook, I had to take a long, hard look at the lifetime I’ve lived with her music.

She was one of the most innovative and distinctive musicians of any genre, ever. She didn’t follow anyone’s rules. “If I’m going to sing like anyone else,” she said, “then I don’t need to sing at all.” She did things with a row of notes that defied convention, logic and gravity. Her voice came from deep inside. She told a story through the twists and bends in a musical line, the pull and push of a phrase.

Billie Holiday’s music taught me that something beautiful could be made from sadness.

She gave away her heart boldly and foolishly, and every time it was bruised or broken, she turned that pain back into something beautiful, in a song. Love is funny or it’s sad, it’s a good thing or it’s bad, she sang, but beautiful. I’ve had my share of that. There was a spring when I practiced Rachmaninoff all day and listened to Billie Holiday at night. I’m a fool to want you, she sang, and I echoed the phrase in my foolish head.

When I was eight years old, Billie Holiday’s music taught me that something beautiful could be made from sadness. For a musician, that is one of the most powerful lessons to learn. It’s what saves us, time and again. She lived a short and troubled life, but the happiness and luck that she did find, she found through her music. And finding your joy and your strength in music is something I do know about. I know what it’s like, when things have fallen to pieces, to put on your satin dress and go onstage, finding the secret power of a woman in a satin dress, pulling your audience in and making them fall in love with the music — just the way I fell in love with Billie Holiday’s songs when I was eight years old.

Her music keeps coming to find me. This year, at night, I’ve been listening to “Strange Fruit,” another sad song for what has been a sad year in America: a year of black men and boys being killed, the massacre in Charleston, black churches burning again in the South. A year of old hatreds and violence exposed, not so far under the surface as we would like to think. I listen to the howl of pain and rage that she pulls out of the last vowel of the last words of the song: A strange and bitter crop, and there are centuries of sadness in her voice. She turns the sadness into something magical, overwhelming, strangely beautiful.

National history. Downes’ grandmothers, Fay (right) and Ivy (left), illustrate for her the racial tensions which continue to wrack the United States.

It’s been hard to hold on to hope this year. I’m raising a caramel-colored boy of my own now, and I would like to think that my parents’ dream can come true for him, but I am afraid that the dream is still out of reach. I’ve been sad, and I’ve turned to music. This time, I’ve gone back to my beginnings, to the music that first taught me how to find the beauty in sadness. I’ve been playing Billie Holiday songs, on my own instrument, with my own musician’s voice reaching back to join hers. I’ve played this music for audiences all over America. I’ve met people who heard Billie sing live in the clubs in Harlem when my father was a little boy, people who were her friends and lost her too soon, people who have lived their lives with her records, as I have. This music has made me new friends, told me new stories, brought back things I thought I’d lost a long time ago. It has brought me home. After all the years, all the travels, all the music, I’ve understood the lesson I’ve learned from Lady Day. That the magic in making music, as in living life, is this: forget about all the definitions and rules you ever learned. Lean back against the launch pad of your history and your experience, your losses and heartaches and joys, to look out into the future, and to make something that is completely your own — maybe something unexpected or indefinable, perhaps complicated, but beautiful. To take a chance. Beautiful to take a chance, and if you fall, you fall / And I’m thinking I wouldn’t mind at all.

This article originally appeared in Listen: Life with Music & Culture, Steinway & Sons’ award-winning magazine.