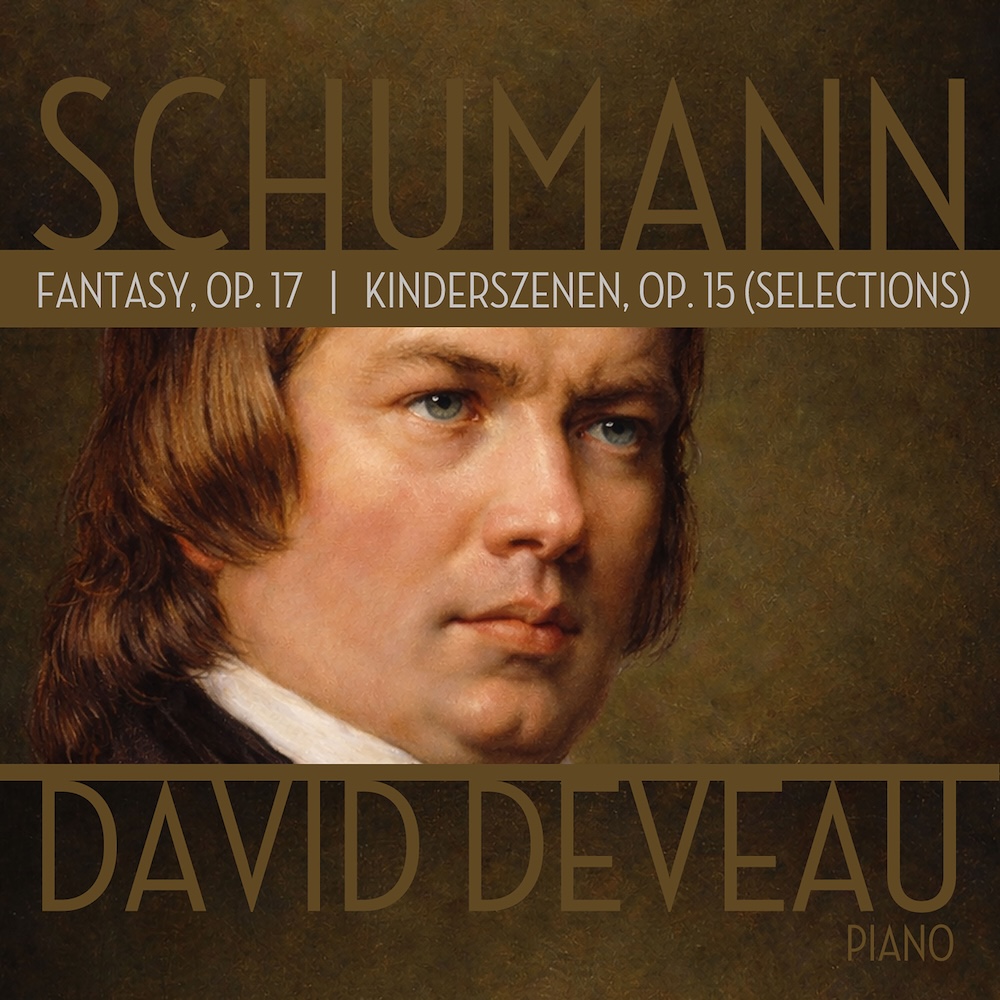

robert Schumann

Fantasy

Kinderszenen (Selections)

David Deveau

For his latest STEINWAY & SONS release pianist David Deveau presents a powerful interpretation of Schumann’s masterwork, the C major Fantasy. He also performs excerpts from Kinderszenen, including the beloved beloved Träumerei.

David Deveau has distinguished himself with expressive and elegant performances of the Romantic piano repertoire

On March 6th, 2026 Steinway & Sons releases pianist David Deveau's recording of Schumann's Fantasy, Op. 17 and selections from Kinderszenen, Op. 15 (STNS 30241). In his liner notes, Deveau discusses the program:

“Theodor Adorno wrote that Robert Schumann’s Fantasy in C major is a work of psychological “twilight”: that prescient moment of acute self-awareness that madness is frighteningly near. “It’s being aware of what it means to lose oneself before being completely abandoned.” This point of view is itself perhaps a bit fantasy-like given that Schumann’s serious mental decline didn’t truly begin for more than a decade hence. The original version of the Op. 17 was completed in 1836 when the composer was just 26. He revised it for publication in 1839 and dedicated it to Franz Liszt. (Liszt, about fourteen years later, would in turn dedicate his own masterpiece for the piano, the Sonata in B minor, to Schumann. By then, Schumann was in his final psychotic collapse and unable to recognize Liszt’s generous return dedication.)

The genesis of the Fantasy has less to do with Liszt and far more to do with Schumann’s enforced separation from his piano teacher’s daughter, Clara Wieck. Clara, nine years Schumann’s junior, was forbidden to see Schumann because her father felt him to be emotionally unstable and an inappropriate, unsuccessful suitor. In addition, Clara was a brilliant young pianist already destined for a major concert career, and Friedrich Wieck wasn’t pleased to imagine his major investment in Clara’s training result in her becoming a mere Hausfrau to Robert. They were separated at Wieck’s insistence for over a year and a half. The love story between Robert and Clara is well known, and the Fantasy is often described as Robert’s tone-poem of yearning and longing for Clara. Indeed, he wrote to Clara that this was his most passionate work to date. The first movement concludes with a reference to the last song in Beethoven’s cycle “An die ferne Geliebte” (To the distant Beloved). But more on this feature later.

Schumann’s original trajectory was as a concert pianist, but his future as performer was curtailed by an irreversible injury to the fourth finger of his right hand (by using a mechanical device intended to strengthen the fingers). Later research into Schumann’s mental illness suggests that, in addition to the finger injury, he suffered from tertiary syphilis, common in the nineteenth century and which was often treated with mercury. Mercury poisoning can cause paralysis of the fingers, then wrists and forearms, resulting in serious weakness or focal dystonia. His personal loss of a virtuoso’s career is posterity’s gain, as Schumann turned full time to composing and literary efforts. His erudite music criticism and observations of then current developments in the music world of the early-mid nineteenth century are indispensable documents.

Schumann’s first twenty-six published works are all for solo piano. These are works of breathtaking originality and invention, from the glittering Moscheles-like Abegg Variations to the lengthy, half-hour cycles of connected miniatures like the Davidsbündler Tänze, Carnaval, Kresleriana and three full-scale sonatas. He composed two sets of fantasy pieces (Opp. 12 and 26), the Humoreske, the Symphonic Études and perhaps the greatest work of all, this C major Fantasy, Op. 17. This blaze of compositional intensity and white-hot inspiration—all written before he was thirty—is unmatched in quantity and consistency by his later output, as great as many individual works are. He had similar periods of staggering creativity—the song-cycle years of 1840-41, the chamber music year of 1842, and he was prodigious throughout his brief, 46-year life. But sadly, Adorno’s observation about the Fantasy, is perhaps better applied to the works of the 1850s, when Schumann’s mental decline and suicide attempt landed him in a psychiatric sanitorium for his final two years, during which time Clara was dissuaded from visiting him. His agitation became unmanageable when she did. In better times before this tragic final chapter, Robert and Clara had eight children, several of whom died young, but others who lived well into the early 20th century. Clara was a true pioneer: after Robert’s death, she was a widowed mother, supporting her family by touring throughout Europe as a virtuoso (and promoting Robert’s works). She was also a fine composer in her own right, and although her output is relatively small, her music is of high quality.

Before Robert’s institutionalization, the young Johannes Brahms had entered the family fold, with Schumann immediately recognizing his great genius even as a provincial twenty-year old from Hamburg. After Robert’s death Clara and Brahms maintained a lifelong and deep friendship, dying within a year of one another at the end of the nineteenth century. There has been much speculation about the exact nature of their relationship, but its important feature is that Clara was sought by Brahms as an honest critic of his works, and she provided this feedback—sometimes fiercely. Brahms, later in life, said that Robert’s nobility and seriousness as an artist was his eternal model, his most important “Vorbild”.

The C major Fantasy began life as a large three-movement sonata quasi fantasia (to borrow from Beethoven’s Op. 27). It was originally conceived as a piece to raise funds for a memorial statue of Beethoven in Bonn. After other publishers refused the piece, Breitkopf & Härtel accepted it, and indeed proceeds were directed to the Bonn effort (to which Liszt ultimately donated the most). In the original version, each of the movements had a title: Ruins, Trophies, Palms. (These were deleted when Breitkopf published the piece.) A major musical alteration was made as well: the ending of the first movement, with its quotation from An die ferne Geliebte served also as the end of the final movement. This material also features a remarkable chordal alteration in the second iteration of the Beethoven song stanza (one which a noted pianist remarked to me sounded like Kurt Weill). I play this altered chord sequence here at the end of the first movement, as it was his original inspiration, and is well worth hearing. Charles Rosen proclaimed that this original ending of the whole composition, with the reprise of the first movement conclusion, was superior. I respectfully disagree, and feel that the ecstatic, climactic series of arpeggi in the revision are truly inspired, and the final climax features the same high A-G interval that opens the entire work, thus coming full circle. The piece’s original ending has been said to reinforce Schumann’s longing for Clara, while the revised ending seems a culmination, a fulfillment.

Musically, the Fantasy features many innovative techniques, including a roiling, boiling distant sixteenth-note storm in the left hand (based on a dominant ninth) which underpins the descending right-hand melody in octaves A-G-F-E-D. This opening, rather like Tristan—another work of great longing—delays harmonic resolution for as long as possible. The C major tonality is implied and felt rather than stated outright. The form of the opening movement is loosely that of a sonata, but the middle section, rather than being a development of the expository ideas, is a new and highly improvisatory one (“Im legenden Ton”). The march-like second movement (in E-flat), features a device Schumann later in life perhaps used to excess: the dotted rhythm. This energetic quasi-sonata-rondo form movement has symmetric outer sections, with a quieter yet restless middle section that moves from relative calm to agitation, and then to a scherzando transition back to the first material. It concludes with a coda marked “viel bewegter’ (much livelier), often attempted at a prestissmo tempo (sometimes to the pianist’s peril). The contrary motion jumps here are infamously treacherous and should probably be practiced blindfolded - or at least looking upward in prayer.

The last movement, back in C major, is a deeply felt nocturne written in two halves of almost equal length, each building to a majestic climax. The extended, revised coda serves as a perfect summation, an outpouring of love that vanquishes all earlier yearning. Three quiet chords bring the piece to a richly satisfying close.

Kinderszenen (Childhood Scenes), Op. 15 was composed during this same creative burst. It, unlike the later Album for the Young, was not intended for children to play but rather as a reminiscence of scenes of childhood. Included here are three, Träumerei (Reverie), Kind im Schlummern (Child in Sleep) and Der Dichter spricht (The Poet speaks). These miniatures show a different aspect of the passionate Schumann, a quieter and reflective one. He himself gave names to these two dueling musical personalities: Eusebius (the dreamer) and Florestan (the firebrand), and can each be heard in his Carnaval, Op. 9 with those precise titles. Throughout Schumann’s musical and literary output these temperamental opposites attract and repel each other, with the composer occasionally even signing the initials E or F at the end of a passage or paragraph. Most often, those initials are hardly necessary, as the writing speaks clearly and eloquently for itself.”

— David Deveau

“For his profound way with Schumann’s Fantasy in C Major, Deveau is well worth seeking out by solo-piano aficionados... The gripping voicings, gripping harmony, mesmerizing bass both chords and lines, entrancing modulations: all were abetted by Deveau’s marvelous pedaling, discrete and discreet. It made for perfect sonic blend and overlap.”

Boston Musical Intelligencer

Album Credits

Schumann: Fantasy, Op. 17; Kinderszenen, Op. 15 (Selections) / David Deveau • STNS 30241

Release Date: 03/06/2026

Recorded December 16-17, 2025 at Thomas Tull Concert Hall, MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Producer: Claude Hobson

Recording/Mastering/Editing: Luke Damrosch

Piano Technician: William Grueb

Piano: Steinway Model D #626736

Executive Producers: Eric Feidner, Jon Feidner

Art Direction: Jackie Fugere

Design: Cover to Cover Design, Anilda Carrasquillo

Project Coordinator: Renée Oakford

Photo of David Deveau: Claude Hobson

About the Artist

This is David Deveau’s fifth release for the Steinway & Sons label. His 2015 recording, Siegfried Idyll, was critically acclaimed in the New York Times and Gramophone, and was listed as one of that year’s ten best classical albums by the Boston Globe. In 2018, Steinway re-issued his recording of Schumann’s Carnaval and Kreisleria. On his 2019 album, Beethoven, Mozart and Harbison, Deveau joined forces with the Borromeo String Quartet for chamber versions of popular classical concertos. His recording of Schubert's Sonatas, D 959 & D 960 was released in 2022.

Deveau has enjoyed a substantial career of over five decades, with appearances on four continents. He has performed as soloist with major orchestras including the Boston, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Houston, Minnesota and Miami symphony orchestras with such conductors as Bernard Haitink, Herbert Blomstedt, John Williams, Michel Plasson, Oliver Knussen, John Harbison and Jose Serebrier. Abroad he has appeared with L’Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse (France) and the Qingdao Symphony (China). His recital appearances include New York’s Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall, Boston’s Jordan Hall, San Francisco’s Herbst Theater, Washington’s Kennedy Center and Phillips Collection, the Shanghai Theater Academy, Beijing’s Forbidden City Concert Hall, and at venues in Japan and Taiwan. He served as Artistic Director of the Rockport (MA) Chamber Music Festival from 1995-2017 and was on the music faculty of MIT for over thirty years. He resides in midcoast Maine.

About Steinway & Sons label

The STEINWAY & SONS music label produces exceptional albums of solo piano music across all genres. The label — a division of STEINWAY & SONS, maker of the world’s finest pianos — is a perfect vessel for producing the finest quality recordings by some of the most talented pianists in the world.